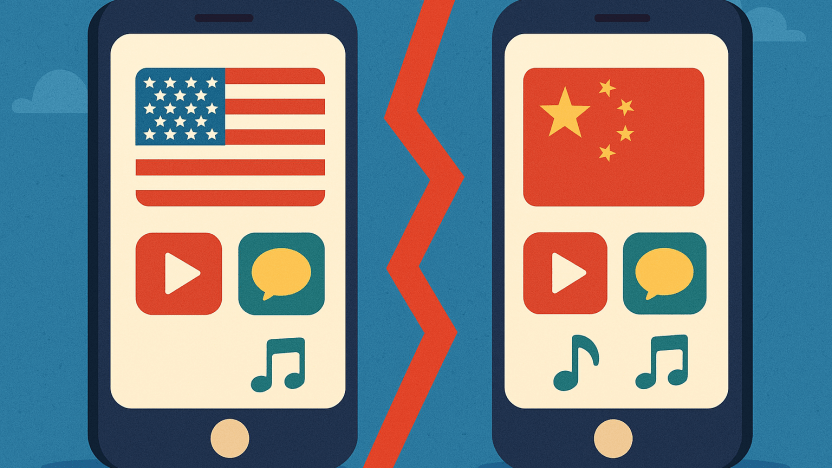

China’s approach to internet governance, often referred to as the “Great Firewall,” has created a unique digital ecosystem where many popular American apps are blocked, leading to the rise of Chinese alternatives. This policy stems from China’s emphasis on cyber sovereignty and information control, creating what is effectively a parallel internet universe.

Why China Blocks Western Apps

The Chinese government restricts access to foreign apps and services for several key reasons:

- Data Security: Concerns about foreign companies collecting and storing Chinese citizens’ data

- Content Control: Desire to monitor and regulate information flow within the country

- Economic Protection: Supporting domestic tech companies and preventing foreign dominance

- Political Control: Maintaining oversight of public discourse and social movements

Popular American Apps and Their Chinese Counterparts

Social Media

- Facebook → WeChat/Weixin & RenRen

- WeChat, originally called Weixin, was launched by Tencent on January 21, 2011, as a simple messaging and photo-sharing app developed by a small team led by Allen Zhang. It quickly gained popularity, surpassing 100 million users within 433 days, prompting Tencent to rebrand it as WeChat in 2012 to appeal to international markets. Over the years, WeChat evolved into a “super app,” integrating features like social networking, mobile payments, and mini-programs, establishing itself as a crucial part of daily life in China and beyond.

- WeChat has evolved beyond social media into a super-app

- Includes payment systems, mini-programs, and government services

- RenRen was once known as “China’s Facebook” but has declined in popularity

- Twitter → Weibo

- Weibo, launched by Sina Corporation on August 14, 2009, emerged in response to the banning of foreign social media platforms like Twitter following the Ürümqi riots. Recognizing a gap in the market, Sina capitalized on this opportunity to create a microblogging site that allowed controlled information sharing within China

- Similar microblogging format

- Heavy integration of multimedia content

- Stronger emphasis on celebrity and influencer culture

Messaging

- WhatsApp → WeChat & QQ

- QQ, originally named OICQ, was developed by Tencent and launched on February 4, 1999, as a response to the popularity of instant messaging services like ICQ. The platform quickly gained traction in China, becoming the most widely used instant messaging service, with over 800 million registered users by 2020.

- WeChat dominates messaging in China

- QQ remains popular, especially among younger users

- Both offer more extensive features than WhatsApp

Search Engines

- Google → Baidu

- Baidu was founded in January 2000 by Robin Li and Eric Xu, emerging from Li’s earlier work on search engine algorithms, notably RankDex, developed in 1996. After raising initial capital from Silicon Valley investors, they launched Baidu.com in 2001, quickly becoming the leading search engine in China by allowing advertisers to bid for ad space

- Baidu commands over 70% of China’s search market

- Specialized for Chinese language and local content

- Integrated with other services like maps and encyclopedias

Video Sharing

- YouTube → Youku & Bilibili

- Youku, founded by Victor Koo in December 2006, initially mirrored YouTube’s model by focusing on user-generated content. However, in 2012, it merged with rival Tudou to form Youku Tudou, shifting its strategy towards professional content and original programming, akin to Hulu or Netflix. Acquired by Alibaba in 2015, Youku has since become a major player in the Chinese video streaming market, emphasizing licensed and original content to attract viewers and advertisers.

- Youku focuses on longer-form content and TV shows

- Bilibili targets younger audiences with animation and gaming content

- Both platforms feature robust content creator ecosystems

E-commerce

- Amazon → Alibaba (Taobao/Tmall) & JD.com

- Alibaba was founded on June 28, 1999, by Jack Ma and 17 co-founders in Ma’s apartment in Hangzhou, China, aiming to create a platform for small and medium-sized enterprises to engage in international trade. The company secured a crucial $25 million investment from Goldman Sachs and SoftBank shortly after its launch, which helped it establish itself in the burgeoning e-commerce market.

- Alibaba’s platforms dominate online retail

- Advanced mobile payment integration

- More social and interactive shopping features

Ride-hailing

- Uber → DiDi

- DiDi Chuxing, founded in June 2012 by Cheng Wei, began as a taxi-hailing app named Didi Dache, created to connect passengers with cabs in real-time. The company rapidly gained market share and merged with rival Kuaidi Dache in 2015, consolidating its position as a dominant player in China’s ride-hailing market. By expanding its services globally and going public in 2021, DiDi has become one of the largest ride-sharing platforms worldwide, serving millions of users across various countries.

- DiDi acquired Uber’s China operations

- More comprehensive transportation options

- Better integration with local payment systems

Impact Analysis on American Apps being blocked

Positive Effects

1. Economic Growth

- Creation of major Chinese tech companies

- Millions of jobs in the domestic tech sector

- Innovation in mobile payments and e-commerce

2. Technological Development

- Development of unique features suited to Chinese users

- Advanced mobile payment infrastructure

- Integration of services (super-apps)

3. Local Market Understanding

- Better adaptation to Chinese consumer preferences

- More effective localization of services

- Faster response to local trends

Negative Effects

1. Information Access

- Limited access to global information

- Creation of information bubbles

- Reduced cross-cultural exchange

2. Competition

- Reduced international competition

- Potential for monopolistic practices

- Limited exposure to global innovation

3. International Business

- Challenges for international companies

- Complicated cross-border operations

- Different standards for data handling

Future Implications of American Apps being banned

The divide between Chinese and Western apps continues to grow, with implications for:

1. Global Internet Governance

- Setting precedents for internet sovereignty

- Influence on other countries’ policies

- Impact on global technical standards

2. Technology Development

- Parallel development paths

- Reduced knowledge sharing

- Potential incompatibility issues

3. Business Operations

- Increasing complexity for global operations

- Need for separate strategies for Chinese market

- Data privacy and security challenges

Conclusion to American Apps being banned

The emergence of Chinese alternatives to American apps represents more than just market competition – it reflects fundamental differences in internet governance philosophies. While this has fostered innovation and economic growth within China, it has also created challenges for global internet integration and cross-cultural exchange. Understanding these parallel digital ecosystems is crucial for businesses, policymakers, and users operating in an increasingly complex digital world.